Following on from the curriculum reforms instated by Michael Gove, starting with the National Curriculum programmes of study for Key Stages 1 to 3, GCSE reform is on the way. D&T, which was missed on the second list of subjects for reform, is due to have new specifications in schools for teaching from September 2016. So it’s time to start the conversation about what D&T examinations should look like.

It’s a big question, so here are some thoughts (unrefined as they are!) about problems, solutions and options…

Problems:

- Impact of prescriptive and categorised assessment criteria on teaching, learning and assessment in schools – initially inferring a linear design process, which many teachers found hard to break with when the Awarding Bodies changed (reduces) the assessment categories and rebalanced the marks for designing and making (back in 2008/9?);

- Too many GCSE options – looks like a good thing, but it causes some confusion as to what D&T is about (i.e. is it about design and technology or is it about ‘materials’);

- Lack of clear progression to Level 3 and beyond – i.e. Different qualification names both within and across Awarding bodies (e.g. GCSE Graphic Products to ‘what?’ at A Level?);

- Lack of clarity/understanding between academic, practical, technical and vocational aspects of design and technological learning – this is a division that our European colleagues don’t seem hold;

- An (over?) reliance on the single, integrated design and make activity at GCSE and A Level, in the past, and in some cases currently – i.e. design and make at GCSE and design and make at A Level (how many times have I heard teachers comment on pupils ‘still’ not getting what a design portfolio is in A2?);

- Teacher perceptions of appropriate assessment models – the OCR innovation challenge (GCSE and A Level Product Design), which is built on research by Richard Kimbell and others at Goldsmiths, does not seem to have gained favour with teachers (is this because it is such a radical departure from what we have seen in recent years?);

- The popularity of problematic D&T GCSEs (e.g. Graphic Products) and vocational courses (e.g. Catering) that divert attention from core D&T practice and activity – I’m not against graphics (by the way), but what is a graphic product? It seems nonsensical to have a qualification that limits possible graphic outcomes to 3D products. Graphic communication is a key skill for designing, but is graphic design better placed within the flexible territory of Art and Design?

- The popularity of making over designing – this is not negative per se, but does manifest as a desire for craft focused assessments or separate practical making D&T qualifications;

- Teacher (quite altruistically) try to get the best marks for their pupils, which can result in formulaic projects and limited D&T – we need to recognise the pressures that they are under and the reasons for this practice, rather than condemn it outright.

Solutions:

- Reduce the number of GCSE options – I am I’m favour of the three part approach, which has been suggested by Andy Mitchell from the D&T Association (see below) – although Andy has gone as far as to suggest on specification that covers all of D&T;

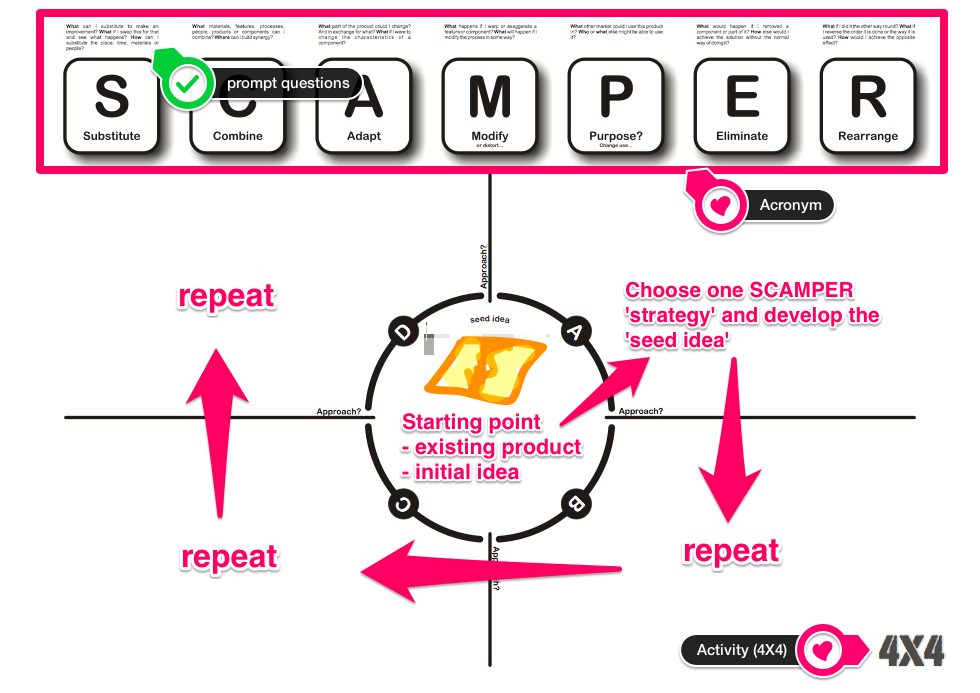

- Radical rethinking of assessment models and assessed D&T activity (i.e. evaluate the impact and usefulness of the current design and make coursework activity and written exams, commonly used in most GCSE specifications);

- Consideration of research regarding assessment of designing, design and make, creativity, etc. (national and international) – I’m thinking particularly of Richard Kimbell (et al);

- Identification of priorities for children (creativity and cognitive, emotional and physical intelligence), education (FE, HE and beyond), society, industry, etc.;

- Encourage graphics specialists and enthusiasts to adopt existing (or new?) Art and Design: Graphic Design GCSE and A Level options – build on existing links between A&D and D&T in FE and HE;

- Encourage D&T departments to develop specifically vocational options alongside existing D&T qualifications – in conjunction with other subject departments and teachers (in particular progression routes relating to STEM careers).

Possible GCSE options:

- One qualification, called Design and technology, with three options [working titles]: (a) Materials (‘compliant’ and ‘resistive’), (b) Food and (c) Control (electronics, mechanics, programmable, etc.) – avoiding Product Design and Engineering, as these imply a vocational focus (i.e. both are careers that learners might choose – I suspect that we would not consider a D&T Catering, so why these?

- Three separate GCSEs with a D&T core: (a) Design and technology: Materials; (b) Design and technology: Food; and (c) Design and technology: Control

Assessment models:

- Rethink the design and make assignment / project – in particular the design portfolio. Alternatives such as the use of sketchbooks, notebooks, journals (including ICT such as blogging, video diaries), alongside a shorter final presentation of the project which would include an artifact (product, system and or service). Note: this might require two or more different sets of assessment criteria, a little like the Level 2 Project or Level 3 Extended Project;

- Removal of the controlled assessment restrictions for coursework conducted over weeks or months;

- Alternative assessments, such as the OCR innovation chalked to assess design creativity;

- Consider the value and content of written D&T examinations – in particular the ‘designing’ aspects.

Just thinking!…