I read an interesting article yesterday (26th April 2013) on Google Glass, in the MIT Technology Review (thanks to David Barlex and Torben Stegg). The author (John Pavius) discusses some of the, potential, technical and social issues with the user interface with Google Glass. However, the most interesting part was a reference to the 20th Century German philosopher Martin Heidegger, who is possibly best know for his writing on tool use.

Pavius takes a slightly dystopian view of the implications of the Google Glass user interface with future ‘technological’ products in the future, which somewhat reflects Heideggar’s leanings. Having said that, I think that he (Heideggar) can teach us something about products. He wrote within a the school of phenomenology, which (very crudely speaking) is concerned with the observation and experience of phenomena (things that occur/happen in human experience).

Heideggar was interested in objects, or more accurately ‘things’: he actually was not particularly keen of objects as a term, inferring a distance, whereas ‘things’ are experienced and meaningful (think that I’ve got that right!?). Two key concepts regarding tools, in heidegarrian philosophy are readiness to hand and presence at hand. These terms describe human beings relationship to and use of tools. Heideggar used the example of the hammer. When a hammer is in use, it becomes an extension of the arm and withdraws from consciousness: this is readiness to hand. Conversely, if the hammer does not function or functions inefficiently, it comes into consciousness and become less effective as a tool (Heideggar takes about ‘broken’ tools): this is presence at hand.

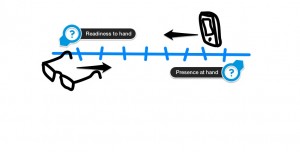

This got me thinking that often when I have read people explaining this concept, it is in terms of tools being one or the other. But what if tools move between the two states? We experience (use) tools (products and/or technologies) in two different ways (or from two different perspectives). Sometimes products are used instinctively and unconsciously, such as spectacles, and they become an extension to our body (readiness to hand). Many technologies are like this when they become ubiquitous and part of how we live and act within our society/culture. On the other extreme, there are products that are very much in our consciousness, but not necessarily because they are ‘broken’. Take, for example, the iPhone: much loved by many despite its perceived flaws. So appears to be a disruptive element in the design of much-loved products that pulls them into consciousness (presence at hand).

This line of argument suggests that products might be ‘positioned’ at a point along a continuum between readiness at hand and presence to hand. This positioning might be contingent on the technology maturity of or adoption of specific technologies by the local culture (and individual), but complex products, such as smart phones, cars and buildings, move in and out of consciousness; so the ‘position’ is not fixed. When I feel the hardness (resistance, even mild discomfort) of my iPhone in my hand and against my ear, I am reminded that it is not part of me, it remains in my consciousness (presence at hand); at the same time functioning as an extension being used unconsciously (readiness to hand).

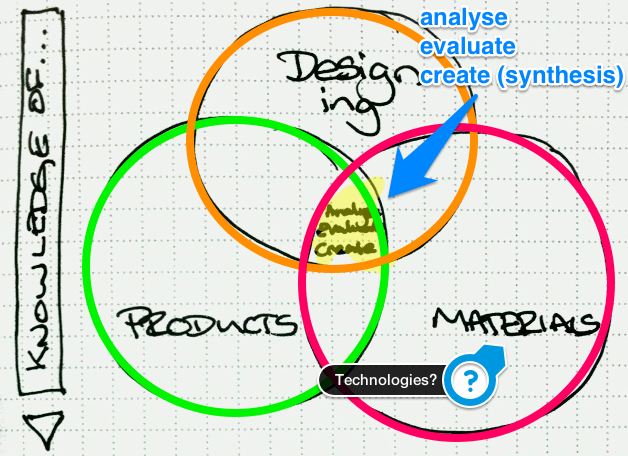

So what are the implications for a philosophy of products or product design? Are disruptive ‘imperfections’ part of people’s emotional attachment to products? Can complex products be simultaneously ready to hand and present at hand? Or do they move in and out of consciousness? Does Heideggar suggest a way to avoid the dystopian view of technology and technological determinism?… [to be continued]